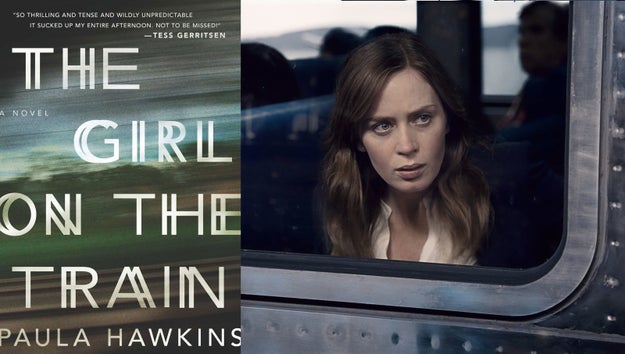

Half an hour into The Girl on the Train, Rachel, played by Emily Blunt, finds herself falling down drunk in the bathroom at Grand Central Station. After drinking vodka out of a water bottle all morning and shivering in the cold, she came back to the station, her cheeks flushed with gin blossoms, her eye makeup smeared beneath her eyes.

Rachel’s been coming into the city from the suburbs every morning as if she has a job — but she doesn’t. She’s just trying to keep up the appearance of normalcy, even though she was fired from her PR job for drinking too much, which happened after her marriage ended because she was drinking too much, which happened because her idea of herself, and her future, had shattered when she couldn’t get pregnant. “The booze broke us,” she explains.

In the bathroom, she takes her phone and records herself telling Anna — her ex-husband’s new wife, the mother of his child — to fuck off. And then she descends into something far darker. Imagining what she’d do if she went to her old house, the house her ex-husband now shares with Anna, she says, “I’d wrap my hand in her long blonde hair, and I’d pull it back,” her slur turning to a scream, “and I’d smash her head all over the floor.”

But The Girl on the Train isn’t really a story of alcoholism, and Rachel doesn’t actually want to kill Anna. Getting drunk just happens to be the only way Rachel can articulate what she can’t when sober: namely, that she’s furious at what her life has become.

The film is the most recent adaptation of the “literary thriller” trend that's dominated the publishing industry for the last five years. But it's also the latest in a long line of texts that channel women’s rage at living under patriarchy. It offers an escapist fantasy, but unlike most fantasies, the escape is not into a more perfect world, just one where women can call bullshit, some more murderously than others, on the increasingly impossible expectations that legislate our lives.

Female rage and despair have an expansive root system through the history of literature, branching through the work of mid- and late-19th century writers like Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Sarah Orne Jewett and Kate Chopin, whose novella, The Awakening, only became part of the high school canon decades after Chopin's death. Originally published in 1899, The Awakening sparked equal parts indignation and praise: “It is sad and mad and bad,” Charles L. Deyo wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “But it is all consummate art.”

The Awakening is broadly about a woman who becomes dissatisfied with her traditional life as a wife, mother, and member of proper society. She takes a lover, experiences something like freedom, and has that freedom taken from her. Unlike Madame Bovary, the book to which it was most often compared, the protagonist is not punished, nor is she killed off by her author. Seeing the options laid before her, she walks into the sea, ending her life on her own terms.

Calling a female character “unlikable” is often just a way of saying she's quit pretending to conform to the contours of proper femininity.

Chopin envisions womanhood not as a world of possibility — of loves found and joys pursued, of blissful partnership and rewarding parenthood, of clever conversation and diverting social engagements — but of impossibility. Not a utopia to pursue, but a dystopia to suffer. That same claustrophobia would manifest in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, published just six years later, and The Age of Innocence, published in 1920; it would be fractured and spread over stream of consciousness in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925) and plunged deep into despair in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963).

What distinguished and sensationalized these books was their oppositionality: They were women’s books, written by women, about women, primarily consumed by women, and offered a bleak counter-narrative to the dominant understanding of the place of women. And even if the protagonists were intensely unlikable, they were immediately psychologically familiar; as Roxane Gay points out, calling a female character “unlikable” is often just a way of saying she's quit pretending to conform to the contours of proper femininity.

These particular narratives resonated and provoked in part because of how effectively they illuminated a particular restlessness, ennui, and deeper sadness hovering in the air during times in which women were expected to be pleased with their lives. In the 1920s, for example, after women won the right to vote and the “New Woman” was on the rise, or during the return to supposedly blissful domesticity in postwar America. Or today, when women should be thrilled with our progress and privilege, but nonetheless find particular pleasure in the idea of misandry.

Of course, women have also historically found escape in cheery romances and weepy melodramas: The uncomplicated pleasures of the utopia often prove a stronger draw than the fraught ones of the unhappy or unlikable woman. Take the late ’90s and 2000s, when the the rom-com and its novelistic equivalent, chick lit, gradually enveloped women’s entertainment. First, there was the bulldozer of Bridget Jones’s Diary, followed by Sex and the City and the books of Jennifer Weiner, and all of their filmed equivalents and knockoffs and offshoots, from The Wedding Planner to Bride Wars, The Devil Wears Prada to Confessions of a Shopaholic.

These texts — all penned by women, if often directed, in filmic form, by men — center on characters who’ve arrived at positions of success and moderate power only to feel like something was missing. They weren’t unhappy, per se, so much as unsatisfied. Yet as each narrative suggested, such dissatisfaction was readily fixable — usually through a combination of shopping, quitting a stressful job, having children, recentering one’s priorities on the home, or, most importantly, finding a man.

The hair color of that dreamy man could change from book to book, as could the weight of the protagonist and the demands of her job. But the overarching message remained the same: It isn’t society’s contradictory expectations that make women unhappy. It’s their independence, their desire for power, their selfish ambition. When they decide to calm down and to “return to what really matters” — e.g., centering one’s entire life on family, relationships, and one’s appearance — contentment will be right around the corner.

These texts were perfect crystallizations of the postfeminist ideology that dominated the time period, and they did blockbuster business — in part because they were simply and tremendously fun. No matter that the plots can feel regressive, even prefeminist: The fantasy they provided was seamless and, as such, incredibly readable and watchable.

The glossy exterior of postfeminism began to smudge sometime in the late 2000s. You can see it in the sourness and barely masked passive-aggression of Bride Wars, in the plotless shitshow of Sex and the City 2 , in the sinking sales of chick lit. Films like Bachelorette and shows like Girls, ostensibly formed in the mold of the rom-com, deliver visions of what I’ve called postfeminist dystopias, highlighting just how destructive and despairing life under postfeminism could be.

Still, it's not as if it suddenly became cool to be a feminist. Rather, the broken promises of postfeminism simply became more visible. The financial crisis spoke truth to the lie that consumption, and the endless credit card debt that accompanied it, could serve as a means to power and happiness. The conservative right’s attempts, many of them successful, to legislate women’s bodies — coupled with the endurance of wage inequality — made it clear that the work of feminism was not something we were remotely “post.”

Slowly, steadily, the dystopia began to devour the postfeminist. You can see the first inklings in 2008, when the first book of Stieg Larsson's Millennium trilogy, translated as The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, began its takeover of the publishing industry. The Swedish title of Larsson’s book was Men Who Hate Women; the book itself was intended as a means of narrativizing a misogyny that Larsson recognized as widespread, if largely unspoken, in his seemingly progressive corner of the world.

From Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl — which has sold more than 15 million copies worldwide — sprung the “Girl + [Blank]” trend.

The English title effectively depoliticized the books, positioning them as pure thrillers while infantilizing and anonymizing their heroine. Yet Larsson’s dark vision, titled and infracted, electrifies Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl (2012). It's most vivid in Flynn’s understanding, through Amy’s voice, of contemporary femininity as full-time masquerade. Reading the book, it's often unclear if Amy Dunne is, indeed, a psychopath — or if she just understands what's necessary to not only play, but win, the deeply fucked game of being a woman today.

From Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl — which has sold more than 15 million copies worldwide — sprung the “Girl + [Blank]” trend, whose most prominent entries are The Girl on the Train (11 million copies worldwide) and Luckiest Girl Alive (optioned by Reese Witherspoon’s production company) but which expands to include All the Missing Girls, The Second Girl, The American Girl, The Girls, Girls on Fire, and many, many more. Some of these titles are more “literary” than others; some take place in the past; some involve teens, others grown adults. Some, like the novels of Megan Abbott, don’t have “girl” or “woman” in the title, yet still spelunk the dark psychological shadows of femininity.

![]()

Broadly speaking, these books are written by white women, center on a white female protagonist — who usually guides the story through first-person narrative — and involve a trauma of some sort, often narrated from some sort of temporal distance. Women, in other words, making sense of their lives, which became irrevocably fucked in some way, at some point. When their husbands started cheating on them, when they failed to have a baby, when they were gang-raped, when they started drinking to avoid their lives, when they started hating themselves and everyone around them.

In these texts, murder is a centrifuge. It’s the result of, or results in, the abuse of women: physical, emotional, psychological, sexual. When women see that abuse clearly, they either become liabilities or murderers themselves, their rage metastasizing into something monstrous. Homicidal rage is just living under patriarchy taken to its logical, if most exceptional, extension.

That extension, that dramatization, is part of what makes these stories both fantasy and so readily consumable. In truth, these women’s lives aren’t so different from our own — the crushing obsession with one’s body and looks and the perception of others, the simultaneous desire to embody the feminine ideal and tell it to fuck right off, the barely contained rage at the impossibility of “having it all.” The protagonists are all achievers in some way, or at least were achievers before things began to sour: They have middle-class homes and college degrees and wear athleisure; they have names like Rachel and Amy and Anna.

And like most readers, they ostensibly have their shit figured out. Unlike most readers, when that shit begins to smell, they spiral out of control. First, and foremost, by eviscerating the standards of femininity to which they’ve held themselves: They call out the empty bliss of constantly disciplining the body into the ideal form; they point to the deep banality and toothlessness of women bitching to each other about the men who discount them.

That’s why the “Cool Girl” passage in Gone Girl has taken on something like canonical significance: When Amy Dunne articulated the tenets of the cool girl — her performance of a femininity laid out for her by men, her hollowness, her desirability, and the simple, devastating fact that men want this woman precisely because she has elided all points of friction — it felt like someone had opened a door that you didn’t even know was there.

There are similar, if less potent, moments in Luckiest Girl Alive. Like when the protagonist — an editor at a women’s magazine — condemns the frivolity of her boss’s consumerism, the blatant eating disorders of her co-workers, and the way planning a wedding cannibalizes women’s lives. No matter that she engages in those activities herself: She knows what she’s doing; she understands the rules of the game. And like those reading her narration, that knowledge elevates and exonerates her. She’s smarter than all that, because she sees, even if that sight is tinged with self-loathing.

![]()

In The Girl on the Train, the knowingness is split between three women, each of whom arrives at it at different points and to different ends. Rachel (Blunt) is ostensibly the main character, but she’s also besieged for most of the book by her own blindness: She sees the world through the haze of her own drunkenness, which is to say, her own crippling shame at the way her life failed to achieve ideals of modern womanhood. She had a husband, Tom, and a house, and a good job, but when she couldn’t have the final puzzle piece — a baby — her world began to crumble around her. The fault, she believes, is her own: She couldn’t get pregnant; she became an alcoholic; she ruined everything.

In her wreckage, Rachel magnetizes toward what she could’ve had: her ex-husband and his new wife’s baby, but also a vision, caught only in glimpses through the train window, of a beautiful, carefree woman with her beautiful, loving husband. That blonde woman represents her own personal chick lit and rom-com ending come to life, and she’s addicted to it.

When Rachel sees that blonde woman kissing a man who's not her husband, it shatters her; when, days later, she learns that the woman has been murdered, it threatens to destroy her. But instead, in her attempt to unravel the murder mystery, she slowly regains clarity. She stops drinking; she stops lying; she goes to therapy. She attempts to see herself, and what happened to her, and the woman she saw on the train — clearly.

Rachel was a drunk, but she wasn’t the aggressive bitch her husband told her she was: Over the course of the narrative, we learn that when she blacked out, Tom abused her, and when she sobered up, he gaslit her into thinking she was the one destroying both of them.

It’s deeply messed-up scenario, but it’s also only a slight exaggeration of the sort of gaslighting that women endure on a daily basis, in which society at large works to convince women that they’re responsible for their own unhappiness. When Rachel finally realizes how Tom’s manipulated her, she stabs him in the throat with a corkscrew — a perfect reflection of the rage women experience when the extent of their manipulation, and their blindness to it, reveals itself.

We also see the perspective of Megan, the blonde woman in Rachel’s rom-com fantasy who’s actually living in her own personal film noir. The beautiful exterior of her life hides a rotten core, or at least a deeply unhappy one. She displaces her tragic past and unsatisfying present by exercising sexual power over men. She hates the suburbs — which she calls “a baby factory" — she’s bored with her husband, she lies to her therapist, and when she gets pregnant and threatens to ruin the perfect life of the man she’s been screwing out of sheer boredom, he murders her.

You could say that murder destroys the domestic idyll that Rachel’s replacement, Anna, created with Tom and their young baby. But Anna herself finishes the work of grinding the corkscrew into Tom’s throat — she kills her own fantasy. In truth, it was already unraveling: You can hear it in the quaver of Anna’s voice when she exclaims that she’s “very busy” spending hours at the farmer’s market so she can puree all of the baby’s food herself, and in the manic fear that calls from an “unknown number” are poised to tear her family apart. She’s terrified, even then, of the ease with which her utopia could crumble.

![]()

One woman dead; one woman a murderer; another woman her accomplice — and all three lives ostensibly destroyed. But apart from the obvious hideousness of Megan’s murder, the film’s ending isn’t tragedy so much as catharsis: two women working together, in however untraditional a way, to rid their life of the toxicity that had contained them. That’s where the pleasure of these texts lies: in the cleansing. Not of the ideological landscape itself, but the lens through which we view it. The escape isn’t to a world better than ours, but to the stark, jagged realities of our world, as it is.

Which is another way of saying that these “thrillers” are deeply rooted in emotional realism: Take away the murder and the manipulative dynamics between men and women, women and their families, women in power and women subject to power, they all remain the same.

Those same dynamics infuse a slew of recent books: In Leave Me, a have-it-all magazine editor and mother of twins becomes so overwhelmed with her Manhattan having-it-all-ness that she doesn’t realize she’s having a heart attack; in Hausfrau, an expat living in Switzerland endures an Awakening-like exploration of the ways domesticity strangles the soul; in The Woman Upstairs, an unmarried woman of a certain age narrates her own rage at the life she never quite lived.

Taken together, these texts don’t make up a genre so much as a mode, a posture, an opposition: If chick lit and rom-coms suggest that everything’s great, these narratives proclaim that everything is very much not. One offers a darling, lovable protagonist, the other a quietly loathable yet deeply recognizable one. One is packaged in pastels, the other in stark black and white. One invests in the idea that love fixes and heals, the other demonstrates all the ways it disassembles. One positions identity as a true expression of one’s inner self, the other, a performance for the benefit of others. One is enveloped by ideology, while the other attempts, in however painful a manner, to make it visible. In short: One produces bullshit; the other calls it.

These narratives aren't wholly progressive, or unproblematically feminist, or even inclusive: The anxieties they depict, and the pleasurable explosions they produce, are largely the provenance of white privileged women. Many women don’t have the mental space to consider the question of “contentment,” because they’re too focused on basic survival. Still, the bulk of pop culture is an expression of the demands and desires of those with the leisure time to enjoy it. That much hasn’t changed for over a century: As a 1899 review for The Awakening averred, “there is no denying the fact that it deals with existent conditions, and without attempting a solution, handles a problem that obtrudes itself only too frequently in the social life of people with whom the question of food and clothing is not the all absorbing one.”

But that does not mean that these problems are not real, or that their exploration should be demeaned or dismissed. At a screening of The Girl on the Train earlier this week, three male critics sitting near me joked about how little the film mattered — how they were just there to see Haley Bennett, who plays Megan, be hot onscreen, how they weren’t even going to take notes. And while the film does not add up to more than the sum of its parts, those dudes' attitude toward The Girl on the Train contributes to the overarching idea that women’s pleasures and fantasies aren’t to be taken seriously — aren’t, in whatever way, a manifestation of lack and need, of melancholy and desire.

To take women’s entertainment seriously, in all of its forms, both light and dark, is to take women’s problems seriously. Which is why The Girl on the Train isn’t just the latest instance of a tired naming trend. Like the rest of the books currently probing the depths of postfeminism, it expresses, with varying degrees of eloquence, provocation, and clarity, the tragedy of contemporary femininity. Ignore it, and the rage that accompanies it, at your peril.